Bulletin – October 2024 Global Economy The ABCs of LGFVs: China’s Local Government Financing Vehicles

- Download 806KB

Abstract

China’s local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) are a key feature – and risk – of China’s infrastructure investment and financing environment. The scale of their debt has consequences for local governments’ fiscal sustainability and for capacity to continue financing infrastructure development. This article reviews progress and challenges in the transformation of LGFVs from local government off-balance sheet financing vehicles into market-driven entities, and estimates the scale and sustainability of their debt burdens at a regional level. Developments in the debt sustainability and investment outlook at China’s LGFVs potentially has implications outside of China due to the importance of LGFVs to financial stability and long-run growth in China.

Introduction

Local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) are state-owned investment companies established by China’s local governments. LGFVs have played a significant role in driving China’s economic growth and investment by financing urban infrastructure development, but these entities have accumulated substantial debts in the process. The original role of LGFVs was to raise debt for local governments, which were liquidity constrained and unable to borrow on their own balance sheets before reforms in the 2010s. Authorities in China have long acknowledged the risks of this opaque off-balance sheet debt and have attempted to reduce the links between LGFVs and local government balance sheets, while transitioning LGFVs to become market-oriented state-owned enterprises. Modern LGFVs have a range of business models, but are most commonly involved in public interest projects such as urban infrastructure construction and renewal, operating utilities or toll-roads, and affordable housing construction. LGFVs continue to struggle with the legacy of off-balance sheet debt, and have had difficulties finding new, profitable business models, that would allow them to stand financially independent of their local governments. This article reviews progress and challenges in the transformation of LGFVs from local government off-balance sheet financing vehicles into market-driven entities and estimates the scale and sustainability of their debt burdens at a regional level.

The role of LGFVs in the Chinese economy

Since the implementation of tax-sharing reforms in 1994, which expanded the tax base and reallocated a large share of revenue to the central government budget, local governments’ share of revenues have been smaller than their spending needs (Graph 1). This led to a short fall in revenue for many local governments (the ‘funding gap’), which at the time of the tax reforms, local governments were not authorised to fill by issuing bonds or directly taking loans from banks. To fill this gap, a popular model was for local governments to set up state-owned enterprises – known as LGFVs – that were permitted to take out loans and issue bonds. These LGFVs were primarily established to finance infrastructure development.[1] As part of banking reforms around the same time as the tax-sharing reforms, local governments were also permitted to establish local banks, and these rapidly increased in number over the next decade (Graph 2). The proliferation of local banks further compounded the rise – and the risks – of LGFVs, as these banks became a major funding source for LGFVs (Liu, Oi and Zhang 2022; Gao, Ru and Tang 2021). Local banks are primarily funded by domestic deposits.

LGFVs were most heavily used as a source of (off-balance sheet) financing following the global financial crisis (GFC). Central authorities actively encouraged local governments to use LGFVs to fund fiscal stimulus, resulting in a dramatic increase in the scale of LGFVs (Shih 2010). However, the expansion of this opaque form of off-budget financing created risks as detailed by central authorities in a 2013 national audit of local government debt (Keohane 2013), largely because LGFVs tended to invest in unprofitable infrastructure projects. Central authorities responded with a two-pronged approach to regulating local government debt. First, they attempted to ‘open the front door’, legalising the direct issuance of bonds by local governments, as well as later granting quotas to local governments to swap LGFV debt into local government bonds. Second, they sought to ‘close the back door’, cracking down on the use of LGFVs as a way of raising off-balance sheet debt. Under new rules issued in 2014, LGFVs were no longer permitted to ‘add government debt’, and local governments were barred from explicitly guaranteeing LGFV debt (State Council 2014).

As a result of these reforms, modern LGFVs have had to seek more varied business models than simply filling local governments’ funding gaps. For example, some LGFVs have transitioned to a legal footing analogous to general state-owned enterprises by eliminating debt that is legally attributable to the local government (known as ‘hidden debt’) and expanding operations in new, more profitable activities. In wealthier provinces like Guangdong, this has been done through shifting hidden debt onto local government balance sheets or paying down debt from LGFVs’ own profits, although for less wealthy provinces, eliminating hidden debt has proven more difficult.[2] Since 2014, LGFVs have become more diversified, investing in sectors ranging from manufacturing, technology and retail, including through venture capital and private equity investments, but have been generally slow to transition to market-oriented companies. As a result, a large stock of existing debt remains on the balance sheets of many LGFVs that have been less successful in finding profitable new business models (Ministry of Finance 2015; Yang 2019). The limited success that LGFVs have had in transitioning to more profitable business models is evident in ongoing declines in their return on assets.

Why does LGFV debt matter?

LGFV debt has increased significantly since 2009, which has increased financial pressure on LGFVs, the local governments that support them, and the local banks that lend to them. Markets perceive that local governments stand behind LGFV debt, regardless of whether the legal responsibility for debt repayment ultimately lies with the local government (as is the case for ‘hidden debt’) or with the LGFV itself. Although the majority of LGFV bonds are owned by local banks, these institutions are unlikely to trade them regularly, meaning the ‘marginal investor’ is more likely to be institutions like insurance funds that are highly sensitive to the perceived safety of these bonds. The perception of local government support means that interest rates on LGFV debt do not adequately reflect the risks of this debt, and therefore more capital is directed to these companies than might be the case in a market system. If capital is misallocated because risk is mis-priced, it will weigh on productivity growth in the economy. Although international investors do not tend to hold LGFV debt, and therefore are not exposed to direct financial spillovers from LGFV debt risks, the global economy is exposed to the impact of capital misallocation on long-run economic growth.

Additionally, from a financial stability perspective, this perception of support generates risks to creditors such as local banks that extend credit to LGFVs at below market interest rates. These creditors would suffer losses if the LGFVs default on loans and perceived government support is unexpectedly withdrawn. The solvency of LGFVs, and the closely related role of local government support for LGFVs, therefore has consequences for the financial stability of local banks, which also tend to be more vulnerable than the large state-owned and joint stock banks (RBA 2023).

The overall debt burden of LGFVs is consequential because LGFVs are a major issuer of debt in Chinese markets (accounting for around 40 per cent of outstanding corporate bonds and the majority of enterprise bonds in 2022). There have been no major LGFV defaults on a public bond (i.e. a bond listed on an exchange or traded in the interbank market, rather than a private placement) to date, but if a LGFV were to default on a public bond, the market may reassess the strength of the local government implicit guarantee not only for that LGFV’s debt, but also the debt of other state-owned enterprises that are perceived to benefit from implicit guarantees. This could lead to a significant repricing of LGFV debt, with potential implications for financial stability.

A significant repricing on public markets could lead to a deterioration in bank asset quality and profitability through either a revaluation of bank assets, or by reducing the refinancing capabilities and therefore LGFVs’ ability to repay their debt. This would be likely to have a larger effect on smaller banks in more indebted and economically weaker regions of China and could inhibit the ability of those banks to supply credit to borrowers or could require bank recapitalisations. Additionally, an LGFV default could also cascade to falling land prices, as LGFVs have historically been a significant buyer of local government land, which, in conjunction with government-led bank recapitalisations could directly affect the revenue- and debt-raising ability, and potentially the solvency, of local governments.

Given bond markets are now pricing a higher degree of government support for LGFVs than in early 2023, the more pressing concern may be the consequences of high LGFV debt burdens in the absence of a default. Debt burdens may weigh on growth by constraining the ability of local government and LGFVs’ to support growth through public spending since local government funds are increasingly allocated to debt repayment. LGFVs may also need to dedicate a greater proportion of capital raised to service existing debt, rather than raising finance to support public interest projects such as infrastructure construction. There may already be signs of this trend: infrastructure FAI growth slowed in 2024 after weak LGFV bond issuance in the first half of the year.

Size of the LGFV debt burden

LGFV debt is significantly larger than official Chinese local government debt at around 50 per cent of GDP, compared with 30 per cent of GDP for official local government debt (Graph 3). We estimate LGFV debt using data on issuance of interest-bearing debt by companies believed to be LGFVs. We focus on interest-bearing debt since this is the type of LGFV debt most comparable to government debt. However, this estimate should be treated as a lower bound of LGFV debt given that our approach does not capture LGFVs that have not issued public bonds and does not include the non-interest-bearing debt of LGFVs. Additionally, prior estimates of the total number of LGFVs significantly exceed the 2,300 LGFVs captured in our analysis (Appendix A).

After the initial burst of post-GFC stimulus delivered through LGFVs, LGFV debt has continued to grow, driven by the continued local government funding gap, soft budget constraints, the need to repay interest on existing debt, and incentives for local officials to boost local growth at the expense of long-run debt accumulation. Accounting for LGFV debt, gross government debt is estimated to be around 90 per cent of GDP. This is larger than the debt of other emerging markets that grew to become developed economies, compared at the same historical point in their development process. For example, in the years that Japan and Korea first exceeded US$12,000 GDP per capita in constant 2015 US dollars (which China first exceeded in 2023), their debt to GDP ratios were 12 and 10 per cent respectively.

LGFV debt is also problematic in how it is distributed due to the uneven distribution of LGFV revenue raising capabilities, combined with the reduced ability of LGFVs in more indebted regions to raise new debt. The proliferation of LGFVs also means that default risks are difficult to monitor, and there may be periods where individual LGFVs may be lacking cash to meet debt servicing needs, even while total local government fiscal resources are sufficient to cover debt servicing. While LGFVs have rarely defaulted on public bonds,[3] they have regularly defaulted on other types of debt such as commercial notes and bank loans, indicating the stress LGFVs face in their day-to-day debt management (Wang 2024).

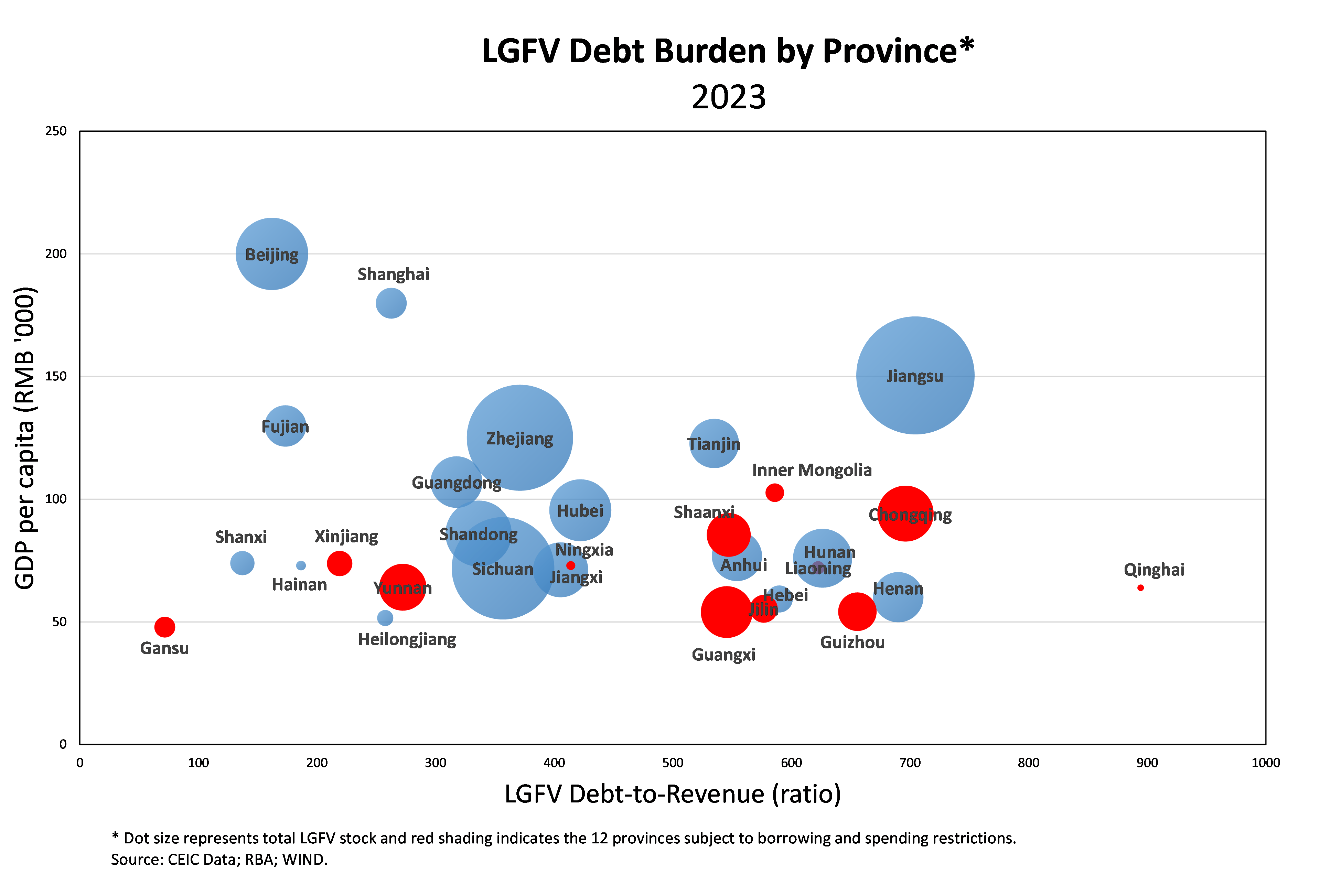

LGFV debt levels are also not evenly distributed among local governments: lower income provinces tend to have greater LGFV debt burdens than higher income provinces (Graph 4). Local governments in economically weaker and more indebted provinces face a higher level of financial stress. These provinces mainly consist of inland regions in the west and north-eastern ‘rust belt’ that have benefited less from the expansion and upgrading of China’s manufacturing and exports, and face greater demographic challenges due to ageing populations. In recognition of the over-indebtedness of certain provinces, authorities have placed restrictions on the ability of 12 provinces to invest in certain new infrastructure projects.

Sustainability of LGFV debt

Many LGFVs do not generate enough cash flow to service debt as they tend to be involved in projects for public welfare, such as financing utilities and infrastructure. LGFVs’ return on assets has been weak and declining for several years (Graph 5). Additionally, LGFV debt financing costs are higher and at shorter tenors than official local government debt. Market economists estimate LGFV financing costs to have been around 5 per cent in 2023, higher than the 3 per cent on official debt, and much higher than the 1.2 per cent LGFV return on assets. The combination of low returns and high financing costs means that LGFVs use a significant share of bond revenue to service existing debt.

These concerns were exacerbated in 2022 as assets operated by LGFVs were adversely affected during COVID-19 lockdowns (such as toll roads and rail). Around half of LGFVs had interest expenses exceeding operational income in 2022. The distribution of this shortfall was geographically uneven: interest payments exceeded operating revenue in 21 of 31 provinces. At the end of February 2023, total government spending on interest payments had grown the fastest of all fiscal spending components (27 per cent in year-ended terms). Interest payments were equivalent to more than 10 per cent of gross fiscal revenue in a third of Chinese cities, and as high as 75 per cent in Lanzhou (in Gansu province). There is also substantial variation in debt service coverage ratios throughout the year, meaning that some local governments may have debt servicing liabilities more than revenues in certain months during the year (Shih and Elkobi 2023).

While local governments have continued to support their LGFVs, avoiding any defaults on public bonds in 2023, fiscal sustainability pressures on local governments themselves have also increased. China’s stringent COVID-19 containment policy and widespread lockdowns, as well as economic weakness in the aftermath of the pandemic, led to an increase in local government spending and a decline in revenue. Land sales revenue – historically the most important source of local government revenue – had contracted by 35 per cent (CNY3 trillion) in 2023 from 2021 levels amid intensifying property sector stress (Graph 6). Local governments increasingly relied on LGFVs to replace developer demand in land auctions and offset falling land sales revenue, as land sales to property developers fell by 53 per cent in 2022. However, increasing pressure from regulators to prevent local governments ‘inflating’ land sales using LGFVs has led to a reduction in this activity, further adding to the decline in land sales revenue. LGFVs themselves have been significantly affected by the decline in the property sector: local government land is often a significant asset for LGFVs, and 25 per cent of LGFVs list property development as their main registered business.

Despite the challenges local governments face in managing their debt burdens, they have continued to service their (and their LGFVs’) debt. Most importantly, transfers from the central government have also supported local government fiscal balances, increasing by 25 per cent between 2021 and 2023. The size of these transfers is significant, equivalent in 2023 to around 45 per cent of local government general public budget revenue and around 95 per cent of central government general budget income (excluding bonds). Second, LGFVs have delayed payments to maintain cash levels, such as by delaying payments to suppliers, defaulting on short-term notes, and missing interest payments on bank loans (Bloomberg News 2023). Media reports have accused some local governments of delaying payments to civil servants (Yuan 2023). Indeed, the Premier’s 2024 Report on the Work of the Government specifically mentioned the need to ensure local governments have the fiscal resources to ensure salaries are paid (Li 2024).

The banking sector has had an important role in helping LGFVs to manage their debt burden. Smaller city and rural commercial banks tend to hold more LGFV debt than the major state-owned banks and joint stock banks due to their regional focus and closer ties with local governments. These banks face a trade-off between profitability and asset quality when considering how to manage losses on lending to LGFVs. Many LGFVs have had loan terms extended by banks or have renegotiated more favourable interest rates on their loans, which weighs on bank profitability. If banks chose not to roll over LGFV debt, they would have to categorise the loans as non-performing and provision the loans accordingly, which could result in many small banks being undercapitalised. The issuance of special bonds for bank recapitalisation increased considerably in 2023 and is indicative of the pressure banks face to continue absorbing losses from LGFVs (Graph 7).

Resolving local government debt issues

Authorities face two fundamental challenges in resolving local government and LGFV debt. First, China’s local governments continue to face a funding gap, exacerbated by the significant loss of land sales revenue in recent years. Fiscal reform to better match local governments’ revenue-raising and expenditure responsibilities is needed to improve fiscal sustainability, local government fiscal discipline and the social safety net (Wingender 2018; Bloomberg News 2024). Authorities are aware of this issue, and in the Third Plenum meeting held in July promised to expand the sources of tax revenue for LGs, raise the central government share of expenditures and increase central transfers to local governments (20th Central Committee 2024). This is a positive development for addressing the root problem in centre-local fiscal relations and progress here will be important to watch.

The second challenge is that although authorities aim to transform LGFVs into market-oriented state-owned enterprises, not all of these companies have an obvious development path to finding a profitable business model. Some LGFVs have found success in businesses related to their core competencies, such as operating existing infrastructure like toll roads, wastewater treatment or urban renewal projects. Other LGFVs have attempted to diversify into businesses unrelated to infrastructure, such as manufacturing, healthcare and software development (Fan, Liu and Zhou 2021).

LGFVs may also act like investment platforms on behalf of local governments: recapitalising local banks, acquiring listed companies and investing in high-tech industries (Xiao, Zhao and Cade 2020). However, this kind of transition is likely easier for LGFVs in developed cities. Additionally, transitioning to a market-oriented investment platform is easier said than done. For example, an LGFV belonging to Weifang City in Shandong Province, which was previously praised for its acquisition activity as an example to follow for other LGFVs, had suffered significant losses on its acquisitions by 2023 (He and Xu 2023). The Third Plenum has promised faster transformation of LGFVs into general state-owned enterprises but did not specify how it would do this (20th Central Committee 2024).

Authorities are balancing addressing local government debt issues with maintaining a reasonable economic growth rate. The challenge is how to reduce the size of local government debt without triggering a repricing of local government debt that threatens financial stability or affects economic activity. Authorities have attempted to diverge from their historical approach to LGFVs in the recent cycle. Typically, tighter LGFV regulation is met with wider spreads and lower bond issuance, as investors react to reduced government support. In this cycle, authorities have simultaneously backstopped LGFVs and reduced the risk of default, while attempting to limit new borrowing by LGFVs. This action has led to narrower spreads and reduced issuance. In this way, authorities are attempting to reduce risks to the broader financial market in renewing the implicit guarantee on LGFVs, while also requiring LGFVs to be more disciplined in issuing new debt. In other words, authorities are attempting to replace market discipline (i.e. higher interest rates in the absence of implicit guarantees) with administrative discipline (i.e. restrictions on LGFV debt issuance). However, while LGFV net bond issuance has declined even as spreads tighten, total debt growth among LGFVs has increased at the start of 2024 (Graph 8) – this may reflect LGFVs substituting bond financing for bank loan financing as restrictions tighten (Graph 9).

While authorities appear to be comfortable with the approach in the recent cycle, there are risks. First, administrative discipline could be ineffective and LGFVs may increase their debt burden. Second, the crackdown on issuance could put too much stress on LGFVs, causing defaults or the need for a significant bailout. Third, the administrative discipline could be too effective, causing a significant decline in infrastructure investment, thereby posing a threat to the economic growth target. To mitigate this risk, authorities have increased central government expenditure on infrastructure investment, such as the CNY1 trillion special bond issuance announced in 2023 for local government infrastructure spending. The ability of local governments to withstand the decrease in LGFV financing while maintaining economic growth will be tested in 2024, as they continue to face substantial bond maturities (Graph 9).

Conclusion

LGFV debt is a major vulnerability in the Chinese financial system because it is large, difficult to measure, backed by assets with low returns and priced on the basis of government support unrelated to LGFVs’ fundamentals. Defaults by individual LGFVs could have systemic implications if they lead investors to reassess the strength of implicit government guarantees in the Chinese financial system more broadly. However, a broader repricing of risk in the Chinese financial system is unlikely to spillover to financial systems beyond China since direct links between China and the global financial system are relatively small (Adams et al 2021).

LGFV debt vulnerabilities and deleveraging are most likely to affect other economies, including Australia, via economic channels. First, infrastructure investment is likely to slow, particularly in heavily indebted provinces where LGFVs are now prohibited from financing new investment of certain kinds. This could weigh on economic growth in the near term. Additionally, authorities have signalled for some time that they prefer economic activity to increasingly be driven by ‘new industries’ related to science, technology and high-tech manufacturing. This means that infrastructure investment is likely to slow in the future. Some LGFVs have indicated that they are diversifying their business models to expand beyond traditional infrastructure investment to focus more on the industrial sector and infrastructure operation (rather than construction).

The authorities’ approach to managing local government and LGFV debt vulnerabilities will also affect long-run growth. The current approach to managing LGFV debt vulnerabilities means that many LGFVs continue to operate despite not having a sustainable business model. Additionally, as the banking sector continues to provide loan forbearance to LGFVs, credit is not being allocated to the most productive uses. As the pressure on the banking sector grows, additional fiscal resources are likely to be allocated to recapitalising local banks, rather than new government investment or consumption. Although this approach to managing LGFV debt vulnerabilities may avoid a disruptive financial shock, it comes at the cost of slower economic growth in the long run.

Appendix A: Estimate of LGFV debt

We estimate LGFV debt using data from the WIND database. Specifically, we use the interest-bearing liabilities of WIND’s list of bond-issuing chengtou (urban investment) companies. We focus on the interest-bearing debt of LGFVs since this is the type of LGFV debt most comparable to government debt. We use a vintage of the WIND LGFV list from 2022, therefore including some LGFVs that have since been recategorised by WIND.

WIND’s list of chengtou companies is intended to approximate a list that Chinese regulators have historically maintained of LGFVs. Presence on regulators’ lists is tied to certain restrictions around financing such as tighter bond issuance restrictions. The regulatory lists are not public and it is likely that the WIND list is not entirely accurate, especially as it only covers bond-issuing LGFVs. For example, in 2013 regulators indicated that China had over 10,000 LGFVs at the time, while our dataset only covers 1,700 for that period (Keohane 2013). At least one LGFV interviewed by the RBA China Office had no outstanding bonds, relying largely on bank financing, and so may not be listed in our dataset. As such, the estimate of LGFV debt is very likely to be an underestimate. However, there may be some inaccuracies with the WIND list that could lead to an overestimate. For example, some companies in the list may no longer exist or have been merged with other companies on the list. There may also be some companies that should not be considered as proper LGFVs (Xu and Mao 2021). On the whole, our estimates are likely to underestimate the scale of LGFV debt, and should be treated as a lower bound.

Endnotes

The authors are from International Department and the RBA China Office. This article was prepared using analysis undertaken in International Department with reference to interviews undertaken by RBA China Office with six LGFVs across four cities. The authors would like to acknowledge Diego May and Serena Russell for their earlier work developing the approach to estimating LGFV debt used in this article, and are grateful for feedback provided by Jarkko Jaaskela, Penny Smith, Chris Kent and Jeremy Lawson. [*]

A popular version of early LGFVs was known as the Wuhu model, named after a city in Anhui province. The model entailed establishing an LGFV by injecting LG-owned land-use rights. The LGFV then borrowed from China Development Bank using the land as collateral and used the proceeds to develop infrastructure on the land. [1]

Hidden debt is specifically debt (usually LGFV debt) that an LG takes on in contravention of the regulations – that is, any debt for which the LG is responsible, raised by means other than through the LG bond quota system. Most forms of hidden debt involve LGs illegally providing a guarantee on LGFV debt, either explicitly or through indirect means like fully backstopping project returns with fiscal funds (China News 2017; National Audit Office 2017). Hidden debt, in the way that authorities use the term, does not refer to all LGFV debt. [2]

Although commentators commonly state that an LGFV has never defaulted on a public bond, this is debatable. A unit of XPCC, a Xinjiang LGFV, defaulted on a bond in 2018 (Zhang and Jia 2018). This did not shake the market’s broader expectation of an implicit guarantee, perhaps because XPCC is considered unique compared with other LGFVs. LGFVs in other provinces have also missed payments on public bonds (Liang and Jia 2019; Duan 2020). [3]

References

20th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (2024), ‘Communique of the Third Plenary Session of the 20th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China’, 19 July.

Adams N, D Jacobs, S Kenny, S Russell and M Sutton (2021), ‘China’s Evolving Financial System and Its Global Importance’, RBA Bulletin, September.

Bloomberg News (2023a), ‘China’s Hidden-Debt Problem Laid Bare in Zunyi City’s Half-Finished Roads, Empty Flats’, 12 July.

Bloomberg News (2023b), ‘China’s LGFV Insiders Say $9 Trillion Debt Problem is Worsening’, 24 August.

Bloomberg News (2024), ‘China’s Fiscal Reforms Need to Help Local Morale, Experts Say’, 8 January.

Chen Y (2020), ‘Does the Government’s Implicit Guarantee Effectively Reduce the Credit Spread of Urban Investment Bonds? – Based on the Regression Results of Bonds with Different Ratings’, Guangxi Quality Supervision Herald, 9, pp 98–99.

China News Network (2017), ‘Audit Commission: 5 Cities and Counties Borrowed 6.432 Billion Yuan of Government Debts in Violation of Regulations’, 8 December.

Duan S (2020), ‘Chengtou’s Faith Continues to Survive the Test: Jilin Tietou Announced Overnight That It Had Completed Bond Payment’, Yicai, 19 August.

Fan J, J Liu and Y Zhou (2021), ‘Investing Like Conglomerates: Is Diversification a Blessing or Curse for China’s Local Governments?’, BIS Working Papers No 920.

Gao H, H Ru and Y Tang (2021), ‘Subnational Debt of China: The Politics–Finance Nexus’, Journal of Financial Economics, 141(3), pp 881–895.

General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China (2015), ‘The General Office of the State Council Forwarded the Notice of the Ministry of Finance, the People’s Bank of China and the China Banking Regulatory Commission on Properly Resolving the Follow-up Financing Issues of Projects under Construction by Local Government Financing Platform Companies’, Document No 40, 15 May.

He X and R Xu (2023), ‘Acquired 7 Companies, 5 Suffered Losses, and 3 Failed to Make Money: The "Exam Results" of Weifang City’s Local State-owned A-share Mergers and Acquisitions’, Shanghai Securities News, 11 July.

Hu Y and W Wu (2018), ‘Local Government Creditworthiness in Chengtou Bonds – Implicit Guarantee or Implicit Worry’, Review of Investment Studies, 9, pp 44–61.

Keohane D (2013), ‘Because the Results of China’s Local Government Debt Audit Just Can’t Come Fast Enough’, Financial Times, 2 October.

Leng C and A Lin (2023), ‘Chinese Investors Rush into Local Government Bonds as Beijing Eases Default Fears’, Financial Times, 22 September.

Li Q (2024), ‘Report on the Work of the Government’, Speech at the Second Session of the 14th National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, 5 March.

Liang H and D Jia (2019), ‘Hohhot Financing Vehicle Narrowly Avoids Bond Default’, Caixin Global, 11 December.

Liu AY, JC Oi and Y Zhang (2022), ‘China’s Local Government Debt: The Grand Bargain’, The China Journal, 87(1), pp 40–71.

Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China (2015), ‘Implementation Opinions of the Ministry of Finance on the Implementation of Quota Management of Local Government Debts’, Document No 225, 21 December.

National Audit Office of the People’s Republic of China (2017), ‘In the Third Quarter of 2017, the Implementation of Major National Policy Measures Was Tracked and Audited’, 8 December.

RBA (Reserve Bank of Australia) (2023), ‘5.1 Focus Topic: Vulnerabilities in China’s Financial System’, Financial Stability Review, October.

Shen X, H Yin, B Zhang and Z Xu (2020), ‘Do Implicit Guarantees Reduce the Spread of Urban Investment Bonds?’, Wuhan Finance, 5, pp 56–64.

Shih V (2010), ‘Big Rock-Candy Mountain’, China Economic Quarterly, 14(2), pp 26–32.

Shih V and J Elkobi (2023), ‘Local Government Debt Dynamics in China’, UC San Diego School of Global Policy and Strategy Report, 27 November.

State Council of the People’s Republic of China (2014), ‘Opinions of the State Council on Strengthening the Management of Local Government Debts’, Document No 43, 2 October.

Wang L (2024), ‘The Risk Resolution of Urban Investment Bonds Needs to be Driven by Policies and Markets’, Financial View Magazine, 29 May.

Wingender P (2018), ‘Intergovernmental Fiscal Reform in China’, IMF Working Paper No 2018/088, 13 April.

Xu J and Mao J (2021), ‘Local Government Financing Vehicles Transformation and Development Research’, China Caixin Press Group, December.

Yang Z (2019), ‘Hidden Debt No. 27 Annual Examination: “The Government Belongs to the Government, and the Enterprise Belongs to the Enterprise”’, 21st Century Business Herald, 17 August.

Yuan S (2023), ‘China’s Cash-strapped Local Governments Can’t Pay Workers on Time’, Al Jazeera, 11 May.

Zhang X and Y Wang (2019), ‘Local Government Debt Management and the Effect of the Government Implicit Guarantee – Analysis based on Bond Market Data’, Securities Market Herald, 1, pp 28–36.

Zhang Y and D Jia (2018), ‘Surprise Default in Xinjiang Raises New Debt Fears’, Caixin Global, 15 August.

Zhong N, S Chen, H Ma and S Wang (2021) ‘The Evolution of Debt Risk of Local Government Financing Platforms – Based on Measuring the Expectation of the ‘Implicit Guarantee’’, China Industrial Economics, 4, pp 5–23.