Bulletin – January 2025 Payments Access to Cash in Australia

- Download 673KB

Abstract

Cash plays an important role in the community as a means of payment, store of value and a backup to electronic payment methods. Because of this, the RBA places a high priority on Australians continuing to have reasonable access to cash services. Since 2017, the closure of bank branches and bank-owned ATMs has led to increased distances to access cash services provided by banks, particularly in regional and remote areas. However, despite the significant reduction in bank-owned cash access points since 2017, the distance that most Australians have to travel to reach the nearest cash withdrawal point has not changed markedly in recent years. This is mainly because of the strong geographic coverage of Bank@Post and independently owned ATMs. As the number of locations where people can access cash has declined, some communities are vulnerable to a further withdrawal of cash services.

Introduction

The use of cash for everyday payments has declined markedly in Australia in recent decades. The RBA’s most recent triennial Consumer Payments Survey (CPS) found that the share of consumer payments made in cash had fallen from around 70 per cent by number in 2007 to 13 per cent in 2022.[1] More timely indicators such as ATM withdrawals, cash-out at the point of sale, and cash moved from retailers to financial institutions via commercial cash depots (cash depot lodgements), suggest that the long-run decline in transactional cash demand accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic but has stabilised in more recent years (Graph 1).

Despite a lower cash share of payments, cash remains an important payment method for many Australians. The 2022 CPS found that 7 per cent of respondents used cash for 80 per cent or more of their in-person transactions (high cash users) (Mulqueeney and Livermore 2023) – this is equivalent to around 1.5 million Australians aged 18 and over. Older Australians and people on lower incomes are more likely to use cash for a high share of their transactions, and some high cash users may have few alternative methods of payment available to them. The 2022 CPS also found that one-quarter of respondents reported that they would experience genuine hardship, or major inconvenience, if cash were hard to access or use (regardless of how intensively they used cash).

For consumers to successfully use cash, they must first be able to access it and then have businesses accept it for purchases (Guttmann, Livermore and Zhang 2023). The RBA is committed to supporting the Australian Government’s objective to ensure cash remains a viable means of payment for those who need or want to use it (RBA 2024). To support this objective, the RBA analyses a range of indicators of cash access, including the number, type and location of cash access points in Australia, and the distance that people have to travel to reach them.

In this article, we analyse developments in the number and type of cash access points in Australia, and the distance to these points for people living in different parts of the country. We also consider additional factors that may influence the ease of access to cash services.

Where can consumers get cash?

Cash access refers to how easily people can withdraw or deposit cash. Cash services are available via a range of methods, including:

- branches owned by authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) – banks, credit unions and building societies – (referred to as ‘ADI branches’ in this article)

- ATMs owned by ADIs or non-ADIs (independent ATM deployers)

- Australia Post’s Bank@Post outlets

- cash-out at the point of sale offered by some retailers (e.g. supermarkets).

We do not examine other methods of accessing cash in this article. The RBA’s Online Banknote Survey suggests that withdrawing cash from ATMs is the most preferred method of accessing cash, followed by cash-out services and ADI branches (Graph 2).

The number of cash access points has been decreasing in Australia for some time. Data from the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) show that the number of ADI branches declined by nearly 50 per cent (3,239 branches) between 2011 and 2024 (Graph 3). The broad pace of branch closures has continued, with 230 branches closing over the year to June 2024. While most ADI branch closures were in major cities, over one-quarter were in regional and remote areas of Australia. Bank@Post continues to have a strong presence across Australia, with the number of outlets having fallen only slightly since 2015.

The number of ATMs has fallen by over one-quarter (or 9,100 machines) since its peak in late 2016, largely because of a decrease in ADI-owned ATMs. Over the same period, independently owned ATMs, which by number have been broadly unchanged, have gained an increasingly large share of the ATM market. ATM numbers continued to fall over the year to June 2024 (by 4 per cent), although the rate at which banks are removing ATMs has slowed in 2024 compared with previous years. Just over 95 per cent of ADI-owned ATM closures since 2023 have occurred in major cities.

Compared with previous RBA analysis of cash access, we expand the sample of cash access points to include large retailers with a national presence that provide cash-out services. Access to cash-out services at the point of sale increases the options for people to withdraw cash, particularly for people living in major cities.

The geographic distribution of cash access points

While the number of cash access points has fallen, the removal of some may not necessarily mean that people find it more difficult to access cash if there is a suitable alternative nearby. A more comprehensive way to assess cash access is to measure the Australian population’s distance to different forms of cash withdrawal and deposit services.

Data and method

We estimate the distance people need to travel to reach their nearest cash access point by applying the method used in Delaney, Finlay and O’Hara (2019) – distances are measured as the shortest distance between two points (i.e. as the crow flies).[2]

Our analysis uses the following data:

- ADIs’ points of presence data from APRA. These data provide the location of all ATMs and branches of ADIs, and all Australia Post Bank@Post outlets.[3] We exclude other face-to-face ADI points, such as business branches, in our analysis as they do not meet APRA’s minimum branch requirements, and may be entirely cashless.

- ATM data from the largest independent ATM deployers in Australia. These data cover around four-fifths of all independently deployed ATMs, so our analysis may slightly underestimate cash access. Compared with data used in Guttmann, Livermore and Zhang (2023) the sample size has increased, which complicates the analysis of distance to independently owned ATMs over time. The sample size is consistent in 2023 and 2024.

- Fee-free ATMs set up in remote Indigenous communities. Under this program coordinated by the Australian Banking Association (ABA), participating commercial banks pay independent deployers to provide fee-free ATMs in remote parts of the Northern Territory, Queensland, Western Australia and South Australia.

- Cash-out services offered by a number of large retailers with a national presence. These data include the location of roughly 2,000 stores that offer cash-out services with withdrawal limits. As the dataset only captures some major retailers who provide known cash-out services, our analysis likely underestimates access to cash-out from all retailers.

- Australian Population Grid 2023 data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). These data present Australia’s population in 2023 in one square kilometre grids.

Distance to access points

Most Australians live reasonably close to cash services (Table 1). As of June 2024, 95 per cent of Australians lived within 4.0 km of an identified cash withdrawal point (ATMs, ADI branches, Bank@Post outlets, and large retailers), and within 5.7 km of a cash deposit point (ADI branches and Bank@Post outlets). The average distance to reach cash services has been little changed over the past year, despite the further reduction in access points, although this observation partly reflects an expanded sample of retailer cash-out points in 2024.

| Type of access point | June 2024 | Change from June 2023 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Distance in kilometres | Number | Distance in kilometres | |||

| 95 per cent(b) | 99 per cent(b) | 95 per cent(b) | 99 per cent(b) | |||

| All withdrawal services(c) | 4.0 | 13.8 | ||||

| ADI withdrawal(d) | 12,349 | 5.6 | 15.8 | −507 | 0.0 | −0.7 |

| – ADI branches | 3,360 | 12.0 | 37.7 | −230 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| – ADI ATMs | 5,476 | 12.2 | 40.8 | −217 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| – Bank@Post outlets | 3,428 | 5.9 | 17.2 | −63 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| All ATMs(d) | 23,769 | 5.2 | 19.6 | −926 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| – Independent ATMs | 14,336 | 6.2 | 25.7 | −288 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Major retailer cash-out | 2,145 | 19.1 | 85.1 | |||

| ADI deposit services(e) | 6,788 | 5.7 | 16.7 | −293 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

|

(a) Distances are calculated using population data at different points in time. The

ABS population data lags the APRA points of presence data by one year and 2024

distances may be revised after the release of the 2024 ABS population data. Sources: ABS; APRA; AusPayNet; Australian Banking Association; ggmap; Google; Independent ATM deployers; RBA; Major retailers. |

||||||

However, there is notable variation in the distance to different types of access points and changes in the distance over time (Graph 4). In June 2024, 95 per cent of Australians lived within 12 km of an ADI branch, around 2 km further than in 2017 (when the APRA points of presence data first became available). The distance most people have to travel to reach a Bank@Post outlet is around half that to ADI branches, despite having a similar number of access points; 95 per cent of the population live within 5.9 km of a Bank@Post outlet, compared with 12 km for ADI branches (Table 1; Graph 4). This distance reflects the strong geographic dispersion of Bank@Post outlets, which offer both withdrawal and deposit services.

ATMs provide the greatest geographic coverage out of all cash access points. As of June 2024, 95 per cent of the population lived within 5.2 km of an ATM (either ADI or independently owned), a small increase from 2023. There is, however, a notable difference in the distance to ADI-owned ATMs (12.2 km) compared with independently owned ATMs (6.2 km). The distance to ADI-owned ATMs has also increased by around 3 km since 2017. These trends partly reflect the decision of some banks to sell parts or all of their off-branch ATM fleets to independent deployers.

Cash-out services offered by retailers increase the number of locations where people can access cash, and some may find it convenient to withdraw cash at the same time as doing their shopping. While the distance to these services is higher on average than for other access points, it is lower in major cities, where the distance is at most 3.1 km for 95 per cent of the population.

Regional distances

The distance to reach the nearest cash withdrawal point increases substantially with the level of remoteness (Graph 5). As of June 2024, 95 per cent of Australians from major cities lived within 1.6 km of an identified cash withdrawal point, while 95 per cent of residents in inner-regional and outer-regional areas resided within 8 km and 16 km of a cash withdrawal point, respectively. This compares with 32 km for people living in remote areas; for those residing in very remote areas, the distance is nearly triple that figure (95 km).

Moreover, the absolute distance to reach ADI-owned cash services for residents in remote areas has increased substantially over time and by significantly more than for those living in major cities (Graph 6). For 95 per cent of the population living in remote areas, the furthest distance they have to travel to reach the nearest ADI-owned branch and ATM has increased by 31 km and 12 km respectively since 2017, alongside further closures of ADI-owned access points. To the extent that people living in relatively remote areas rely more heavily on cash than those living in urban areas, particularly as a backup means of payment, the withdrawal of cash access points is likely to have a greater impact on those communities.[4] However, the distance to access all services – including healthcare, retail and public transport – not just cash services, is generally greater for residents in remote areas.

While the distance to access ADI-owned cash services is substantially lower for Australians living in major cities, the proportional increase in distance has been larger than for regional and remote areas. Since 2017, the maximum distance that 95 per cent of the population living in major cities have to travel to reach ADI-owned ATMs and branches has increased by 70 per cent and 25 per cent respectively, compared with 5 per cent and 13 per cent for people in remote areas (Graph 6). These changes indicate that options for accessing cash have also shifted for those residing in more urban areas.

Other indicators of cash access

While the distance that people have to travel to reach cash services is a useful indicator of cash access, there are other factors that influence the ease with which Australians can access cash now and in the future. These include the vulnerability of certain communities to a further removal of cash access points, including face-to-face banking services, as well as the substitutability of available cash services alongside further closures of certain access points.

Vulnerabilities in cash access

The state of cash access is vulnerable to the further removal of cash access points in regions with few nearby alternatives. We find that these vulnerabilities are particularly prevalent for face-to-face cash access points and those living in regional and remote communities.

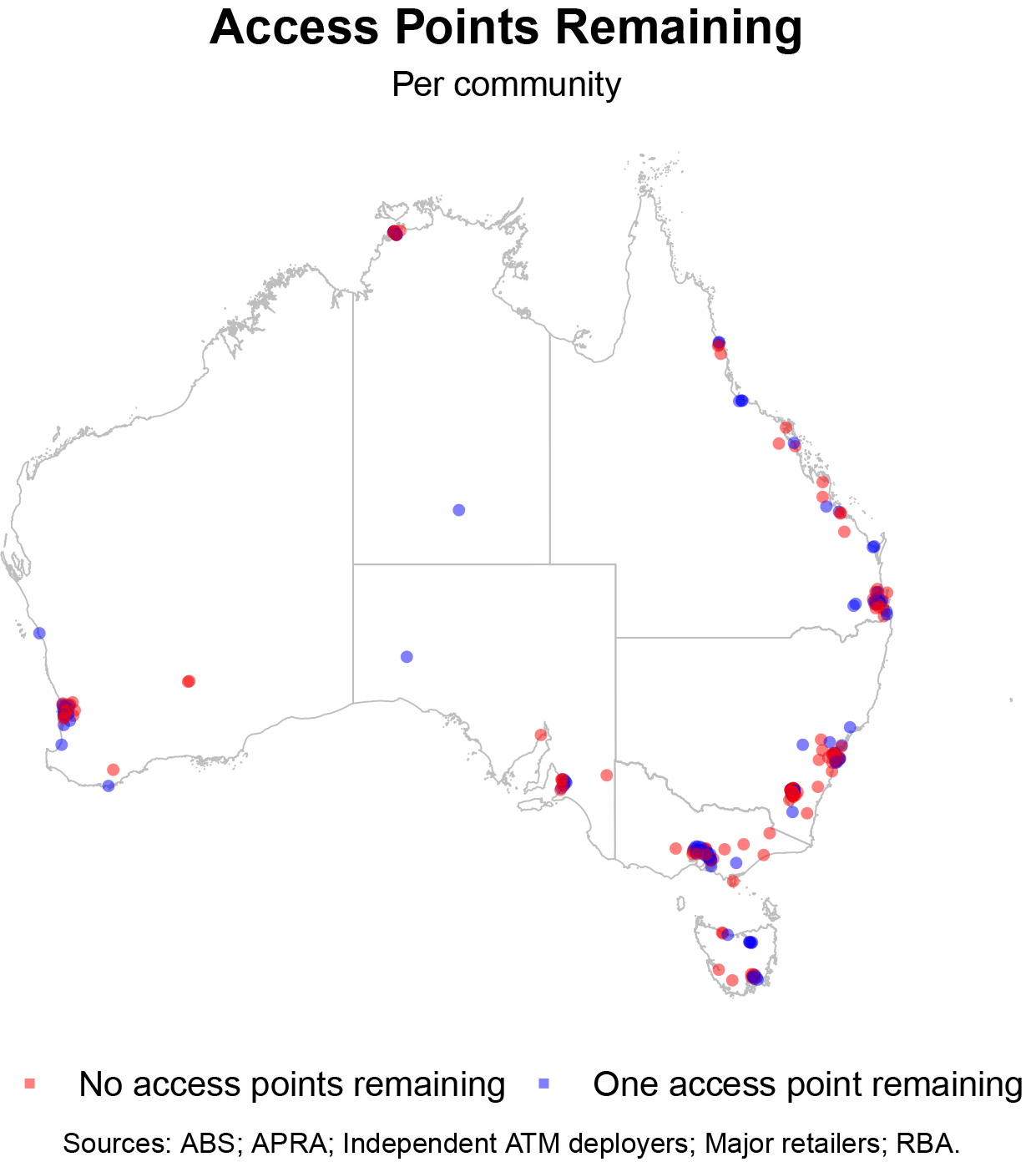

We define communities using the ABS Statistical Area Level 2 (SA2) classification, which is designed to represent communities that interact together socially and economically.[5] Of the roughly 2,400 communities we have identified in Australia, there are around 180 without any cash access points and 120 with just one cash withdrawal point (Figure 1). Of the communities without an access point, the majority are located in major cities or inner regional areas with close alternatives in neighbouring areas. As we do not have an exhaustive list of retail cash-out access points in Australia, it is possible that some of these communities have a local store that provides cash-out at the point of sale.

Most remote communities appear to have at least one cash access point; however, their population tends to be more isolated from alternative access points. Therefore, if someone’s nearest cash access point was temporarily unavailable or is removed altogether, they would face a significantly greater difficulty to reach their next closest cash access point (Caddy and Zhang 2021). The 2022 CPS found that respondents from regional and remote areas reported greater inconvenience accessing cash services compared with the 2019 CPS due to a fall in the number of cash access points and the distance to the next alternative point (Livermore et al 2023).

In addition, there is an increasing number of communities without face-to-face banking services, which disproportionately affects people who rely on in-person support to withdraw or deposit cash, as well as businesses that require over-the-counter deposit-taking services. We look at the share of all communities in each remoteness area that have either one face-to-face banking service remaining or no face-to-face banking services remaining (Graph 7). Around one-fifth of communities in outer regional and remote areas of Australia have no Bank@Post or ADI branches, compared with about one-third of communities in major cities. Around one-fifth of communities in inner regional and very remote areas have only one face-to-face access point remaining. In the vast majority of cases, the last face-to-face cash access point is Bank@Post.

Substitutability of cash access services

The closure of certain access points may have prompted consumers to switch to alternative service types to withdraw or deposit cash. However, cash access points are not always fully substitutable in the services they offer, the customers they can serve and the cost to the consumer for using the service. As such, the composition of cash access points across regions raises important considerations for assessing how easily Australians can access cash services, particularly in more remote areas where there are fewer suitable substitutes nearby.

Bank@Post accounts for most of face-to-face cash access points in outer regional and remote areas, while services are more evenly split between Bank@Post and ADI branches in major cities (Graph 8). However, some Bank@Post outlets do not function as a full replacement for ADI-owned branches or ATMs; not all ADIs participate in Bank@Post; and withdrawal and deposit limits at Bank@Post vary. Some communities may also not be sufficiently aware of cash services provided by Bank@Post (Treasury 2022). In addition, the fees charged for accessing cash services over the counter may vary between Bank@Post and ADI branches. While Bank@Post does not charge for cash services, some participating ADIs may impose separate fees on their customers to access this service; and some ADIs have recently introduced a charge to customers for cash services at their branches or announced an intention to do so.

ADI-owned ATMs are less prevalent in remote and very remote areas, although this is mitigated by the presence of ABA fee-free ATMs (Graph 8). Nevertheless, most ATMs across regions are independently owned, and are more likely to charge customers a fee to access their services compared with ADI-owned ATMs. This could act as a barrier for financially vulnerable people and deter some individuals from accessing cash. In addition, ATMs (both ADI and independently owned) may have different capabilities, such as the ability to deposit cash and cheques, cardless cash and accessibility services (e.g. language translation). Some ATMs may also be inaccessible at certain hours if they are inside a shopping centre, pub or another venue.

Likewise, major retailers are not accessible outside of trading hours. Retailer cash-outs typically require the customer to make a purchase in store to withdraw cash and are subject to a withdrawal limit that is lower than all other service channels. Nevertheless, retailers offer cash-out services for the convenience of their customers and at no additional cost. These services also represent a small share of cash service channels, particularly in more remote areas.

In terms of deposit services, consumers and businesses have fewer alternatives available compared with withdrawal services. While certain deposit-taking ATMs can provide greater accessibility hours than ADI branches or Bank@Post, some business customers may still require access to face-to-face deposit services. Face-to-face banking services are useful for some businesses handling cash as they offer instant and secure deposits and withdrawals, often with higher limits than ATMs, and provide staff assistance to resolve any potential issues arising from cash transactions. If businesses find it difficult to deposit their takings, it may discourage them from accepting payments in cash.

Conclusion

Maintaining adequate access to cash in Australia is important as cash is relied on by a significant number of Australians to make their everyday payments and participate in the economy. Cash is also widely held as a store-of-wealth and plays a role as a backup to electronic payments. While the overall distance to the nearest cash withdrawal point has not changed materially for most Australians since 2017, distances vary significantly by remoteness level. Moreover, some regions are vulnerable to a further removal of cash access points, including face-to-face banking services, and residents may need to use alternative cash service types that may not fully meet their needs.

Many other countries are facing similar challenges. In response, governments and central banks overseas have implemented (or are considering) a range of policy and legislative measures to protect consumer and business access to cash. These responses largely place specific obligations on banks and financial institutions as the providers of cash services. In November 2024, the Australian Government announced an intention to mandate businesses supplying essential goods and services to accept cash, with exemptions for small businesses (Treasury 2024a). The Treasury is consulting on the proposed mandate to understand the needs of cash users and the impact on businesses, and to seek views on cash distribution and access to cash (Treasury 2024b). The mandate is proposed to commence from 1 January 2026. Given the importance of cash in the payments system, the RBA will continue monitoring and evaluating the cash access landscape in Australia.

Endnotes

The authors are from Note Issue Department. [*]

The 2022 CPS was conducted over October to early December 2022, during the COVID-19 pandemic. See Nguyen and Watson (2023) for findings. [1]

We use the geo-coordinates for each access point and the ABS Australian Population Grid 2023 to calculate the straight-line distance. [2]

To be classified as a branch in the APRA Points of Presence collection, branches do not need to provide cash withdrawal services, but they must accept cash deposits. Given some branches may not offer cash withdrawals, our distance estimates may slightly overestimate the distance to withdrawal services from bank branches. [3]

The report on the inquiry into bank closures in regional Australia found that people residing in regional and remote areas are more likely to be socio-economically disadvantaged, have lower levels of digital inclusion, and are more prone to natural disasters that can limit the ability to use digital payments – all of these characteristics can be associated with a higher reliance on cash as a payment method (RRATRC 2024). [4]

In the 2021 Census, there were about 2,400 communities in Australia, with a population range of 3,000 to 25,000 people. [5]

References

Caddy J and Z Zhang (2021), ‘How Far Do Australians Need to Travel to Access Cash?’, RBA Bulletin, June.

Delaney L, R Finlay and A O’Hara (2019), ‘Cash Withdrawal Symptoms’, RBA Bulletin, June.

Guttman R, T Livermore and Z Zhang (2023), ‘The Cash-use Cycle in Australia’, RBA Bulletin, March.

Livermore T, J Mulqueeney, T Nguyen and B Watson (2023), ‘The Evolution of Consumer Payments in Australia: Results from the 2022 Consumer Payments Survey’, RBA Research Discussion Paper No 2023-08.

Mulqueeney J and T Livermore (2023), ‘Cash Use and Attitudes in Australia’, RBA Bulletin, June.

Nguyen T and B Watson (2023), ‘Consumer Payment Behaviour in Australia’, RBA Bulletin, June.

RBA (Reserve Bank of Australia) (2024), ‘Corporate Plan’, August.

RRATRC (Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee) (2024), ‘Bank Closures in Regional Australia: Protecting the Future of Regional Banking’, Report, May.

Treasury (2022), ‘Regional Banking Taskforce’, Final Report, September.

Treasury (2024a), ‘Ensuring the Future of Cash and Next Steps in Phasing Out Cheques’, Media Release, 18 November.

Treasury (2024b), ‘Next Steps in Ensuring the Future of Cash’, Media Release, 20 December.